Sometimes a chance encounter opens up whole worlds. Such was the case for me when I stumbled upon a literary review in a French bookstore.

I discovered the review because of a play. Yasmina Reza’s 1995 L’homme du hasard (The Unexpected Man) is a sort of comic fairy tale about Martha, a woman traveling by train from Paris to Frankfurt. Martha finds herself alone in a compartment with her favorite novelist (a man), one of whose books is in her handbag. Ages ago, in the winter of 2001, a couple of French acquaintances took me to see the play at the Théâtre de l’Atelier in Montmartre, where it was enjoying a successful second run:

Having already lived for several months in France by that point, I could follow along easily enough. The play enchanted me. And although I was then unaware of his stature, prolific film actor Philippe Noiret’s performance as the bitter novelist Parsky made a lasting impression.

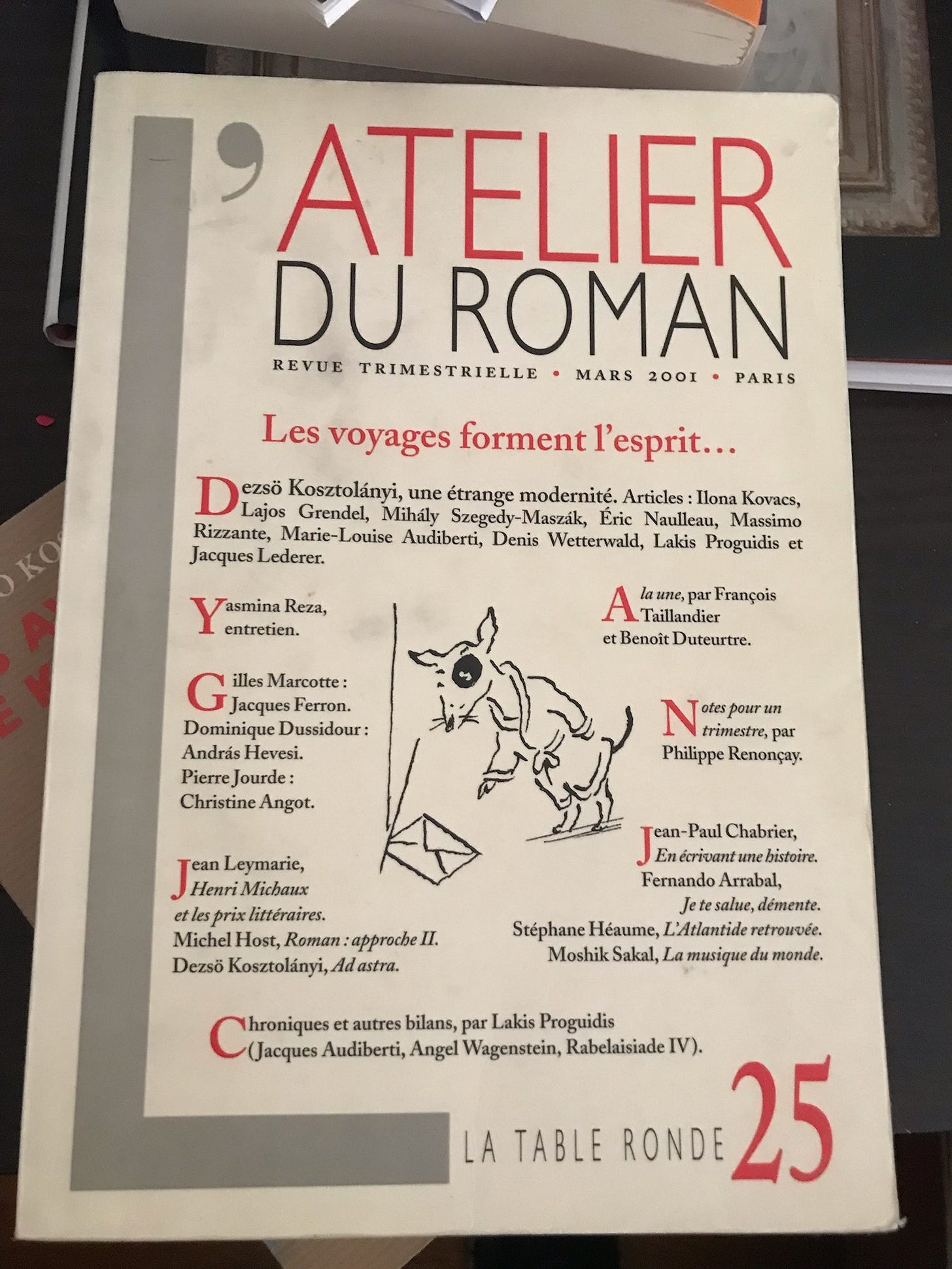

On my next trip to the bookstore, I was on the lookout for anything having to do with Reza, who (as I soon found out) was known for her 1994 hit play “‘Art,’” about three men whose longstanding friendship is fractured when one of them shells out thousands for a Malevich-like abstract canvas (white with white stripes) and begins to style himself an art connoisseur. As I browsed the shelves, I stumbled upon a quarterly literary review that featured an interview with Reza. It was called L’Atelier du roman (“The Workshop of the Novel/The Novelist’s Workshop”), a title seemingly calculated to enlist my sympathies. I found the review’s design and layout appealing. And the style of the playful drawing on the cover, depicting a dog in a bathrobe stooping to pick up a letter, was somehow familiar. . .

I bought issue 25 and took it back to my little apartment. The interview with Reza proved to be both more leisurely and more fascinating than I had hoped, delving deeply into the playwright’s background in music (her father was an aspiring conductor, she herself ranks music above the other arts and has a preference for pre-romantic compositions such as Bach’s Art of the Fugue), the division in her work between plays and novels, the often advanced age of her characters, and her definition of her own works as “funny tragedies,” among other topics.

The interview was conducted by the founder and editor of L’Atelier du roman, the Franco-Greek literary critic Lakis Proguidis, a former engineer who has lived a colorful life. Proguidis spent five years in prison in Greece after joining the opposition party in 1967, the year the military took over the country. It was in his prison cell that he read Milan Kundera’s 1967 novel The Joke, which helped him decide to leave his home country. In Paris, where he settled in 1980, Proguidis would become Kundera’s only doctoral student ever (as far as I know). He was also among the happy few to attend the great novelist’s clandestine seminars.

Over the years Proguidis has published brilliant book-length essays about Rabelais, the Polish novelist Gombrowicz, and the Greek novelist Papadiamantis (the subject of his doctoral dissertation). He has written a book in collaboration with the late French novelist and French Academy member Michel Déon. His interview with Michel Houellebecq is included in the latter’s Interventions 2020. But wonderful though his output as a literary critic has been, I think it’s fair to say that his greatest contribution to contemporary literary culture has been the founding and editing of L’Atelier. Here’s what Lakis says about the review in an interview with Dominique Dussidour, which can be found in full on L’Atelier’s website:

DD: Lakis, can you explain how the Atelier du roman, the only review to my knowledge entirely devoted to the novel, was born?

LP: After I turned thirty I fell in love with the novels of Witold Gombrowicz. And as happens to all those who fall in love with an oeuvre, I immediately became interested in the author’s life. It was then that I learned, among many other interesting things of course, that Gombrowicz considered literary cafés to be essential places for literary life. In his Diary he comes back to this question several times. He frequented the literary cafes of Warsaw before the war. He tried to start a few in Buenos Aires during his Argentinian period. When he came to settle in France in 1964, he discovered, to his great disappointment, that the era of literary cafés had come to an end.

In 1987 I started to write an essay on Gombrowicz’s novels. It was while working on it that I felt that I should do something—yes, love comes with duties—to remedy Gombrowicz’s disappointment. Do what? Start a literary café? I was in love, but I wasn’t crazy… Suppose I created a literary review infused with the spirit of the literary cafés of yesteryear, a review that would function like a literary café? That was the initial idea.

What is a literary café? It’s a place where people come together regularly to talk, exchange ideas, catch up with one another, laugh and joke, while drinking wine and smoking cigarettes with their colleagues, in this case writers. The Atelier du roman was born of this desire to create a space where practitioners of the novel could meet.To create a literary café, there must be regulars. On this point, I was lucky. From 1981 to 1993 I took part in the seminar on the Central European novel (Kafka, Broch, Déry, Gombrowicz, Kis…) that Milan Kundera gave at the Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales. In 1992, when, with the help of Yves Hersant, Director of Studies at the Ecole, I took the first steps toward finding a publisher. I also shared with Kundera and four students my intention of founding a review devoted to the novel. Their enthusiasm and support were immediate. Thus was born the first nucleus of contributors and friends of the review, a nucleus that is still active. Since then, it has been considerably enlarged. Today nearly five hundred writers from around the world have published articles in the Atelier du roman.

Those writers include well-known novelists like Kundera, Houellebecq, Martin Amis, Günter Grass, Emmanuel Carrère, Philippe Muray, Kenzaburô Ôé, and Ernesto Sabato, among others, but also many lesser known or completely unknown writers (including yours truly) who love the art of the novel and are interested in its future. With input from friends and regular contributors, Proguidis and his wife, Doris, set the theme for each issue, which is organized around a novel, a novelist, a country, or a literary question. In the case of issue 25, the focus fell on Hungarian novelist Dezsö Kosztolanyi (1885-1936). I had never heard of Kosztolanyi, but at the bookstore I found a collection of his short stories, translated into French:

The first story in the collection finds the impoverished Kornél Esti journeying homeward from Paris after a year abroad as a student. It describes his ordeal in an ultra-refined restaurant in Zurich, which he enters by mistake in search of an inexpensive bite to eat. Another relates the demise of Esti’s bowler hat, which he esteems “the noblest of habiliments” and mourns with due solemnity; yet another the dreadful predicament into which Esti is plunged when a society lady whose immense manuscript he has promised to evaluate (a task that he has been putting off for months) finally corners him into giving his detailed opinion of her novel, unaware that he has yet to read even one word of it. With their playful humor and taste for both the beautiful and the absurd, these stories, too, enchanted me, just as Reza’s play had.

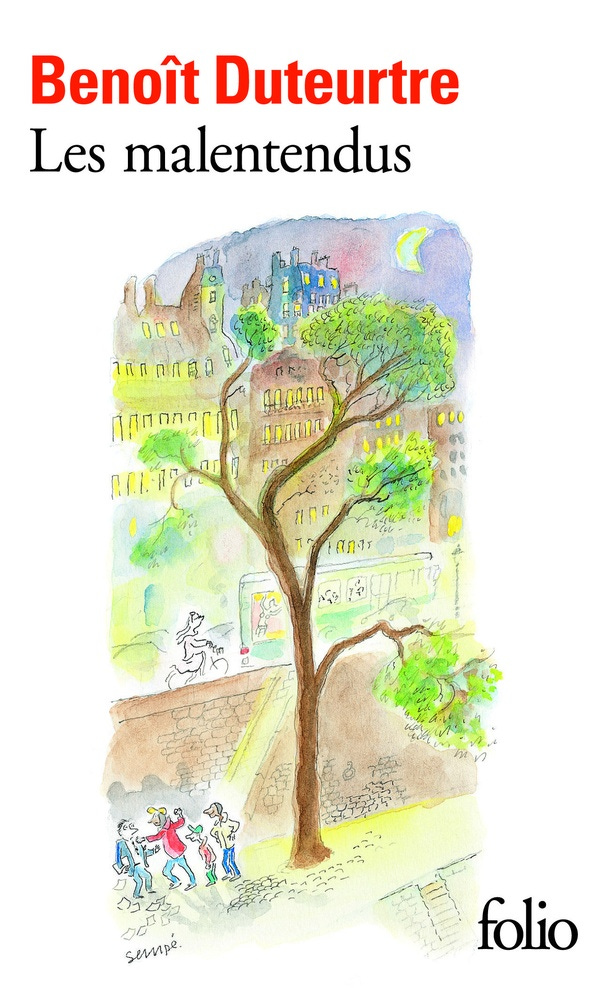

Through issue 25 of L’Atelier du roman, I also became acquainted with the work of French novelist Benoît Duteurtre, who for years wrote regular, endearingly miscellaneous columns (or “chroniques”) for the review (and still did on occasion up until his untimely death in July 2024):

Samuel Beckett and Guy Debord were among Duteurtre’s early admirers. The novelist, music critic, and provocateur was the great-grandson of French President René Coty, a close friend of both Milan Kundera and Michel Houellebecq, and is in my view one of the French writers of the last three decades whose oeuvre is likely to last. Anyone who wants to grasp the social phenomena that have shaped modern France over the last half century could do worse than read Duteurtre’s novels, which, without lapsing into invective, describe the country’s internal contradictions, subcultures, absurd public rituals, and techno-bureaucratic dysfunction while expressing a frank nostalgia for a vanishing cultural patrimony. It’s as if Jacques Tati had been reborn as a novelist a generation later.

A couple of Duteurtre’s books have been translated into English by Melville House—hats off to Melville for this. Sadly, though, neither The Little Girl and the Cigarette nor the novella Customer Service represents the author’s best work. I’m fond of Duteurtre’s 1997 short story collection Drôle de Temps (which translates as “Weird Weather,” but also as “Strange/Funny Times”). It includes a story that’s become something of a cult classic in France, about a young middle-manager who gets trapped in a mysteriously malfunctioning automatic public toilet in Paris on his way to an important business meeting. Le Voyage en France (“The Voyage to France”) is a gentle satire about an American besotted with Monet, Debussy, and the Belle Époque who discovers that technological and social mutations have transformed everything from urban architecture to the railroad lines in the country of his dreams.

Among all Duteurtre’s novels, Les pieds dans l’eau (2008), which strings together memories of childhood and adolescence on the Normandy coast in an almost Proustian mode, is perhaps especially deserving of translation. Though its personal tone represents a departure from the satirical mode of previous works, I think it’s arguably the author’s masterpiece. But an enterprising publishing house might also translate Tout doit disparaître (1992), a picaresque that follows a faux naïf protagonist in his quest to become a journalist, or Les Malentendus (2009), which begins memorably with the demolition of a sinister suburban housing project called The City of the Future and continues with a scene in which an ambitious young member of the Socialist Party expresses solidarity with some Arab youth in the midst of being mugged by them:

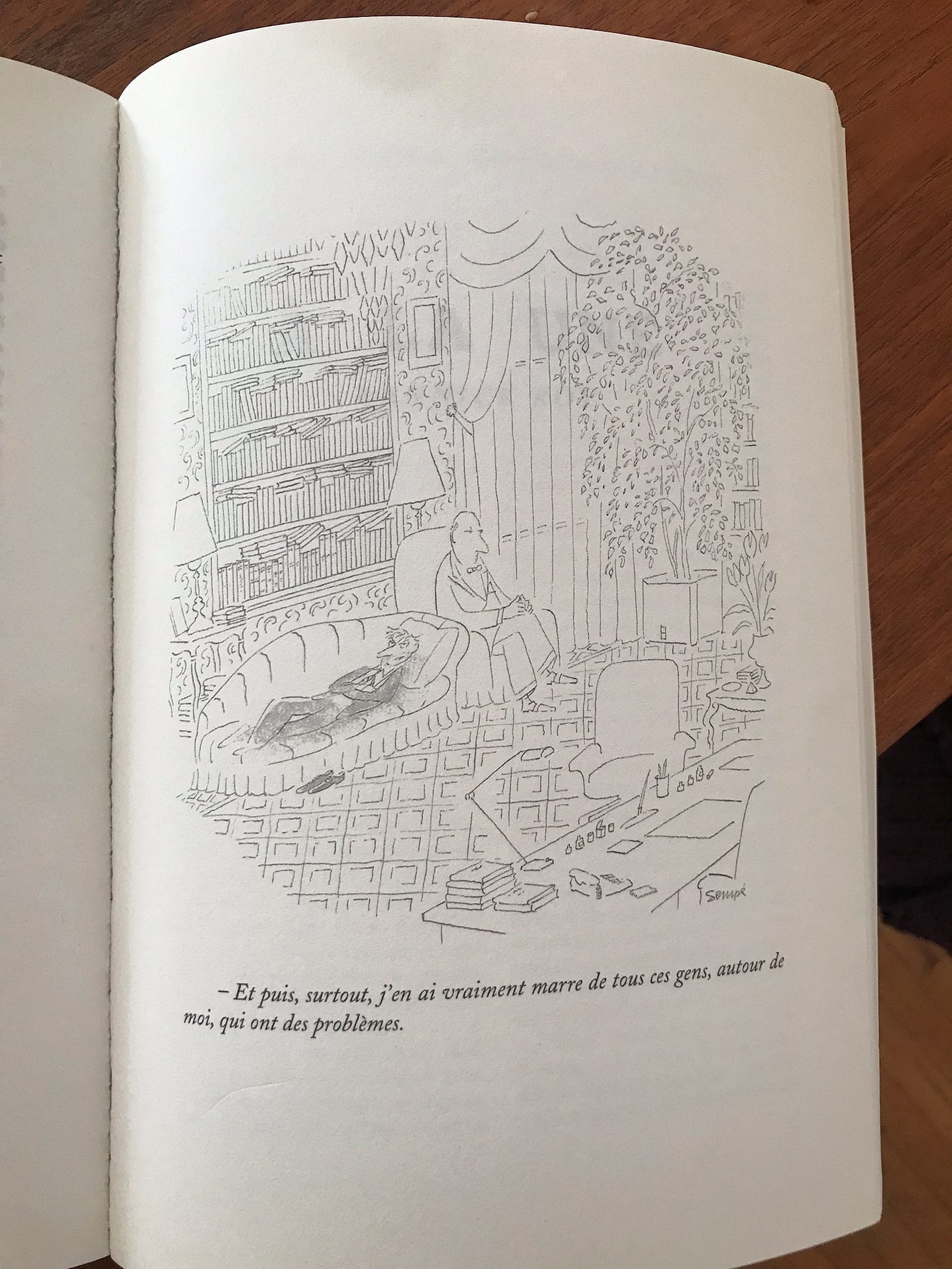

The great illustrator and cartoonist Jean-Jacques Sempé (1932-2022), who drew dozens of covers for The New Yorker and may be best known for collaborating with René Goscinny on Le Petit Nicolas, provided cover illustrations for several of Duteurtre’s novels—and for many if not most issues of L’Atelier du roman as well, including the bathrobe-clad dog on the cover of issue 25, but the first drawing in a multi-part sequence about the dog’s amorous misadventures at and after a masked ball. Sempé’s cartoons bring the review alive, and I can imagine someone subscribing simply for the pleasure of perusing them:

The charm of Sempé’s drawing may help to explain why, by the time of my happy first encounter with L’Atelier in 2001, the review had been around since 1993—already exceptional longevity for a literary review—and why, amazingly, it continues to flourish today, in 2025, almost a quarter century later. But Sempé is only one part of the equation. At some point, in Part 2, I want to give a tour of one of the review’s issues, including its cover, table of contents, illustrations, and a handful of its articles, to show how it embodies Proguidis’s vision of a review that “functions like a literary café.”