I had the pleasure of meeting novelist and screenwriter Alberto Vignati through a mutual friend while he was in Los Angeles a few months ago. We enjoyed a wide-ranging conversation over lunch, and I later asked him if he would be willing to respond to a few questions about Girard and novel-writing. He graciously agreed.

Born in Milan in 1991, winner of the Campiello Giovani Prize for emerging writers, Vignati studied screenwriting at USC Film School and is the author of two novels, most recently Hedonia (Mondadori, 2024), a thriller about Nora, a thirty-year-old teacher who finds herself investigating the unsettling disappearance of a student. Vignati, who lives in Rome, is an avid reader of René Girard, whose ideas inform Hedonia. He says:

“At the basis of Hedonia is the question of what violence is, its necessity, and what place it occupies in our lives. Even more, how social media exploit this need . . . .”

We conducted the interview below by email. Alberto reflects on his beginnings as a writer, the differences between Italian and American literary culture, the question of writing fiction after Girard, and how his training as a screenwriter has shaped his approach to writing novels. I hope you enjoy his rich and thoughtful answers as much as I did.

You are a short story writer, a screenwriter, and a novelist. Can you say a few words about your short story writing, how that helped you to land at USC’s film school, and what prompted your decision to start writing novels?

AV: I began writing short stories for two reasons. First, as a teenager, I found myself immersed in short stories by authors like Poe, Dahl, Pushkin, Calvino, Tommaso Landolfi, and, above all, Dino Buzzati. Second, it was easier to find fiction awards for short stories, and writing one felt less daunting than attempting a novel or a screenplay.

After years trying to write a good short story and being selected for several awards without ever winning, I finally felt I had an idea for a truly strong short story. I wrote it and submitted it to Italy's most prestigious award for young writers, the Campiello Giovani, which aims to promote emerging talent. In 2012, I was selected, and this time, I won.

Years later, when I applied to USC's film school, my creative resume included this award. I believe it made a small difference, or at least, that’s what I was told.

You are the author of a thriller recently published by one of the biggest Italian houses—but I believe you've written another novel as well. Can you say a word or two about each book, what common concerns they share, and how they differ?

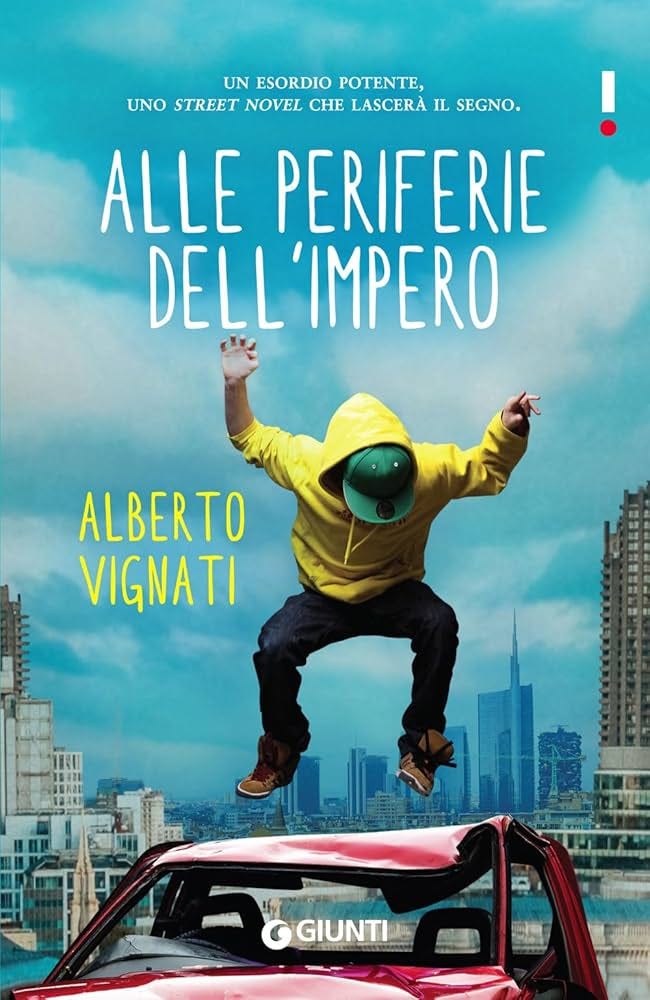

AV: My first novel, Alle periferie dell’Impero (To the Borders of the Empire), is heavily inspired by the short story that won the Campiello Prize. I expanded it into a full-length novel, which was published by Giunti and marketed as a young adult book.

The story is set in the suburbs of Milan, my hometown, and follows Joseph, an Afro-Italian high school student, who begins tutoring Giuseppe, a younger boy who never leaves his bedroom. One day, however, Giuseppe knocks on Joseph’s door and reveals that his family is involved in the mafia, asking Joseph for protection. Meanwhile, Joseph is preparing for the Maturità, the final exams at the end of high school.

In some ways, the novel feels more immature, even though I put significant effort into developing its structure. I’m satisfied with how it turned out, though if I have one regret, it’s that I was still living in LA when it was published, so I didn’t promote it as much as I would have liked.

Hedonia, on the other hand, is more thought-out. I worked on it for about seven years, a period during which I matured personally—I got married and had a son. I believe these life experiences reshaped my perspective on the world. Additionally, I encountered the work of René Girard, which provided a clearer direction for my intellectual exploration of the nature of evil and human violence.

What are some important differences between Italian and American literary culture in your view? Which Italian authors have meant a lot to you? Any American authors (or directors, screenwriters, etc.)?

AV: I’ll give you an example I was thinking about the other day, which probably explains what I used to think about American culture in general and American writers in particular. I have a friend who’s obsessed with Japanese culture, and as is common with people who have a passion for Japan, he believes the Japanese are the best at everything. He especially loves manga – I’d say that’s where his fascination with Japan began. He doesn’t care about Marvel, DC, or Zerocalcare, because he doesn’t like comic books; he likes manga.

For a long time, I had a similar mindset when it came to American writers, both novelists and screenwriters. I didn’t just like novels; I liked American novels. And I didn’t just enjoy TV shows and movies; I only liked American TV shows and movies.

I alternated between reading David Foster Wallace and Beau Willimon, Elmore Leonard and Nora Ephron, or Vince Gilligan, but I also enjoyed more popular writers like Michael Connelly, whom I admire greatly. It’s always hard to find a common thread between such different writers, but in general, I’d say that when I read an American writer, I’m looking for the ability to craft a clear plot with believable, enjoyable twists. I also seek a certain feeling—a general sense of melancholy toward life, mixed with a vague sense of purpose, if not optimism. I believe this is something unique to American writers (think of Flannery O'Connor, Cormac McCarthy, or John Fante).

As for Italian writers, I try to stay up to date with what’s being published. Rejecting modern Italian literature outright would be narrow-minded, though it’s hard for me to feel the same passion for it. That said, I believe that Pier Vittorio Tondelli and Giovanni Testori, especially Testori due to his exploration of the suburbs of Milan, have had an impact on me. The same goes for Scerbanenco, who helped introduce the crime genre to Italian literature. As I mentioned, I devoured Dino Buzzati’s short stories, and in recent years, I’ve enjoyed Antonio Tabucchi and Giorgio Fontana.

Recently, though, I’ve started reading mainly philosophers, and they all happen to be French. Besides René Girard, I’ve been particularly drawn to Simone Weil and Henry Le Saux.

René Girard's thought has played a role in your thinking about the novel, as I understand it. His theories were of help to you especially when writing your most recent novel. How did you discover his work? Which books did you read first and which are your favorite? Do you prefer his writing on literature or his writing on anthropology and Christianity?

AV: While writing Hedonia, I frequently discussed ideas with a friend of mine, Giulio Maspero, a college professor of Dogmatic Theology. I remember him urging me to read René Girard for quite some time, but for some reason, I never really took his advice. I bought The Scapegoat, read the first two pages, and thought it was too complicated for me to grasp. Months later, the book ended up in my hands by accident, and I decided to give it another try—mainly because I didn’t like the idea of not understanding something. So, I started again, and I’ve been reading Girard ever since.

After The Scapegoat, I delved into Violence and the Sacred, and then I decided to read all of his shorter works before tackling Things Hidden. I went through I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, Job: The Victim of His People, Achever Clausewitz, Anorexia and Mimetic Desire, and also a conversation with Gianni Vattimo (Verità o fede debole), and A Long Argument, a discussion with Pierpaolo Antonello and De Castro Rocha. I saved Deceit, Desire and the Novel for last, as I was more drawn to Girard’s anthropological insights than his literary criticism.

My connection to Girard deepened through his three main works: Violence and the Sacred, Things Hidden, and The Scapegoat. That said, Job: The Victim of His People remains one of my favorites; Girard’s interpretation of the story of Job is truly groundbreaking.

Many authors, from Kundera and Coetzee to Elif Batuman and Matthias Énard, have cited Girard as an influence. Some regard the influence as quite positive, others are more ambivalent. Batuman even said that if what Girard says about the novel is true, there's no point to writing novels. Which camp are you in--those who see Girard as a guide, or those who see him as a barrier to writing fiction--and why?

AV: I encountered Girard only recently in my journey as a writer, so I was already in the process of writing Hedonia when I first read The Scapegoat. Finding Girard was, in a way, liberating. He provided me with a vocabulary of meanings I had been desperately seeking. As you know, writing is difficult. It often feels like being in a dark room with your hands stretched out, trying to find something to hold onto. Girard’s work was the faint light that helped me find a direction. I’m specifically referring to the “anthropological” side of his work—everything related to human dynamics, the creation of rituals, religions, and the role of violence in our lives. I believe it is an endless source of stories.

Regarding the "literary" side of Girard’s work, I understand that it might be perceived as a rigid framework. One could ask, what space is left for a creative writer if all fiction simply reduces itself to repeating the same pattern of desire between characters? And if the novel is meant to reveal something about reality, what more can be uncovered that Girard hasn’t already revealed?

I’ll try to answer these questions, and I hope my responses are as thoughtful and insightful as your question.

For the first objection, the same can be said for any framework someone adopts. Of course, Girard’s theory is more profound than something like Save the Cat or McKee’s Story, as it operates on a different level. But from the perspective of a writer facing a blank page, it’s just one more voice in your head, keeping your structure or your characters grounded. It’s one more famished monster you must feed with your own blood. Yet, when you reach the end of a story, you realize that all the frameworks, beasts, and second thoughts helped you avoid writing something overly clichéd or naïve.

For the second objection, I have a problem subscribing to a specific literary theory because I don’t think that’s the way anyone should approach writing. Criticism exists to analyze something that has already been written, not to dictate how something should be created. Girard’s theory is brilliant for reading works like Dostoyevsky’s or The Book of Job, but I’m not sure how useful it is for planning a story from scratch. Writing a story is more so about concrete problems of abstract characters, than abstract problems of concrete characters.

And aren’t we sure that there are areas of reality where Girard seems to be silent? I dare to ask. He speaks to us of rivalry and envy, but what about their opposite? What about the seemingly unstoppable feeling of empathy between human beings? Yes, we compete with one another, but what about the moments of genuine care for our neighbor that transcend time and space? Was that born with Christianity or the Bible? It cannot be. Girard offers an unprecedented approach to the problem of Evil. But in doing so, he pushes us to another set of questions that are worth exploring: where does true love come from? And isn’t the quest for this answer worth writing a novel?

In the US it is sometimes said that there is a division between literature that seeks to effect social change and literature that is concerned only with beauty and art. Do you feel any sympathy for either side? Is there a way to escape this binary?

AV: It’s an interesting way to look at the state of the novel today. Personally, I’m not sure we need to divide novels into these two categories. To me, writing is about grappling with our current time and society. Hedonia was my attempt to explore themes that are both current and societal. I’m not sure if my goal was to inspire social change, as that seems like too grand a view of literature. But certainly, I wanted to provoke questions about how we engage with social networks and how the dynamics of desire, as studied by Girard, can be seen in the everyday use of these platforms.

Has your training as a screenwriter helped you to write novels? Do you think this training would be beneficial to other novelists? What advice would you offer?

AV: Training and working as a screenwriter has profoundly shaped the way I view stories. There’s a popular adage that writers can be divided into two types: architects and gardeners. Architects meticulously plan everything, outlining each plot twist before they start writing, while gardeners begin the writing process and discover the story as they go. I deeply admire gardeners, but I’m afraid I’m an architect at heart. It’s how I was taught to approach storytelling, and it’s what feels most comfortable to me. I can’t begin a story without knowing the end of the first act, the midpoint, and the resolution of the third act. These can evolve as I write, but I need a clear overall arc and a trajectory for my characters to follow.

I also believe that writing is rewriting, which is quintessentially a screenwriter thing to think. I’ve learned that novelists, at least in Italy, don’t rewrite their work as much as screenwriters do. This difference is the aspect of writing novels I dislike the most: the romanticized idea of the writer as an artist, inspired by some muse or divine force. The notion that a writer receives their story as Moses did the Ten Commandments, untouched and untouchable, feels misguided to me. It’s a view that elevates the author beyond critique, as if the story is channeled through them from some higher power. To me, this is both illogical and anti-artistic.

Art, in my view, is far grittier. It’s closer to the image of an artisan chiseling away at marble, sweating for every inch in a dusty workshop, and perfecting their craft through failure and commitment. Writing is a process of constant learning and improvement.

When I read something I enjoy, I can’t help but break it down, beat by beat, to understand how the story works. Everyone has their own idea of fun, but for me, analyzing an episode of Breaking Bad or dissecting a book from the Lincoln Lawyer series is pure enjoyment. The same applies to more “literary” works—I love exploring how and why they succeed, breaking them down as I would any well-crafted narrative.